teenage engineering OP-XY

The OP-XY raises the bar for grooveboxes, with its deep and immediate workflow, incredible sequencer, oodles of connectivity, ultra-premium hardware and a strong lineup of synth engines and samplers. As a true successor to the OP-Z, it delivers (almost) everything its predecessor did and then some.

Pros

- Incredible hardware

- One of the best hardware sequencers out there

- Synth engines and sequencers sound fantastic

- Extensive connectivity

Cons

- Some missing features and bugs still present

- Artificial note limits make creating complex pieces challenging

- Your wallet won't forgive you for this one

The OP-Z was never as in vogue as the OP-1. Despite its deep and capable sequencing workflow and swathes of connectivity and expandability options (especially for such a pocketable device) all at an attractive $599 price, it was perhaps the lack of a display, and therefore of a traditional UI that never made it quite as desirable.

Shortly after the OP-1 field had released, rumors about a redesigned OP-Z, supposedly in the works, started circulating. It simply made sense. The community was intrigued, if a tad scared: would this would-be device join the high-class ranks of teenage engineering’s field system, out of reach for many of the OP-Z’s loyal connoisseurs, or would it stay true to the original with its price tag?

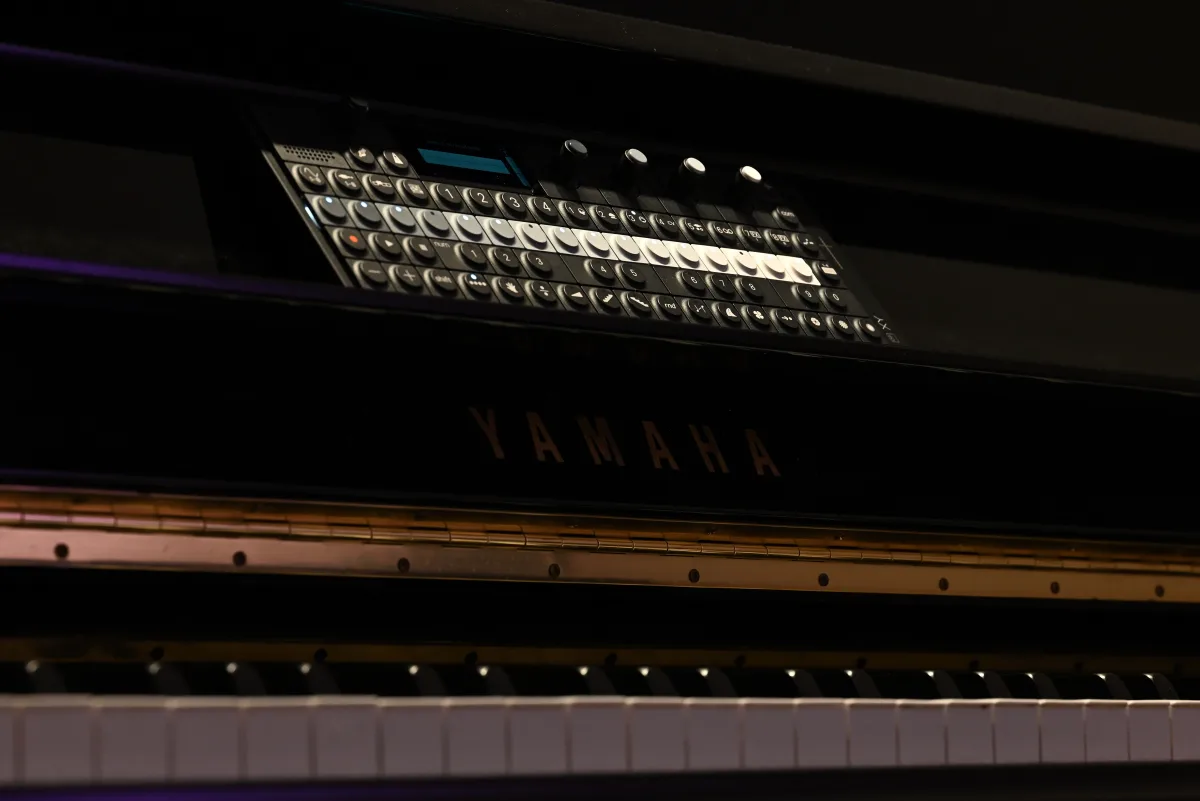

Enter OP-XY. Its striking visual design is more or less what you’d get by running an OP-1 field through a monochrome filter. Gothified, if you will. Sexy even, according to teenage engineering’s seriously flamboyant marketing. Hopefully, the new black anodization will be able to withstand the wear and tear of getting out and about while retaining its alluring looks. Darker finishes usually don’t hide scratches too well.

But upon closer inspection, it’s not quite the same face underneath all the new makeup. The keyboard area has lost some height with a dedicated row of keys for step sequencing now sitting above it. Various never-seen-before symbols are scattered all over the place and — woah — some buttons now feature little LEDs? It’s OP-Z-meets-OP-1-field! And yes, to answer that burning question from two paragraphs ago: the OP-XY is the newest member of the company’s field system, making its hefty price tag, $2299, not all that surprising.

Let’s begin by taking a look at the workflow that’s at the heart of this classy new groovebox. Before we get to that, we’d like to thank the team at teenage engineering for sending over a review unit. As with all our reviews, any and all opinions are strictly our own — no third party had any influence in the creation of the article.

The OP-XY workflow: sequencing at heart

The OP-XY and OP-Z’s are cut from the same cloth. Portable, battery-powered, sleek and lightweight. Were we to ignore all the bells and whistles, it’s the same core step sequencing workflow that remains across both. Tap a note on the keyboard, select the step(s) that it should trigger on, and build up various patterns using the built-in synth engines or spice things up with a sample or two.

This is, of course, nothing like the OP-1, which relies on an intentionally limited set of tools and an audio-first workflow, advocating for as many “happy little accidents” as possible. It’s as if the units’ inverted color schemes represent their opposing design philosophies — fuzzy, imperfect analog tape machine versus a proudly digital, surgically precise sequencer.

Back to our XYZs — the similarities between the two continue. Both are 16-track machines, with an even split between eight musical and eight utility tracks (these are dubbed auxiliary or control tracks, depending on the device). On the XY, the latter are where you’ll find external MIDI, CV and external options, various types of effects and the Brain — the XY’s unique (and pretty clever) transposition system. Both units feature arranging tools for chaining together patterns into more complete compositions and include basic mixing and mastering tools, as well as two FX busses with per-track send amounts.

Both the XY and the Z are based around a fundamentally multi-timbral sound engine. The OP-Z has preset per-track polyphony limits: the four rhythmic sampler tracks and the arpeggiator track offer 2 voices, the bass track is monophonic, the lead track offers up to 3 and the chord track caps at 6 voices. The OP-XY is more flexible, with a total of 24 freely assignable voices — though with a hard-coded 8-voice-per-track hard limit.

But there’s one seemingly minor difference that makes the experience feel nothing alike and lets the OP-XY offer much more depth: the inclusion of a screen. Together with its larger, more tactile and comfortable buttons, the OP-XY feel like a real instrument. It feels more direct and immediate than its predecessor. The decision to drop the OP-Z’s screen in favor of a tethered app had its merits, but not without sacrificing some ease-of-use. Using the Z standalone takes time to master — getting used to all the colorful blinky lights being your only source of guidance comes with a steep learning curve. Ultimately, it’s the lack of a screen that limited how much functionality the OP-Z could have offered without its interface becoming something straight out of a bomb defusing operation. Thanks to its expanded UI capabilities, the OP-XY can take the rest of its features a lot further as well.

That’s not to say that we don’t miss some of the OP-Z’s design choices. For example, with all track controls in the same place, the Z made it possible to adjust a track’s levels and panning right alongside all of its other parameters. There are multiple instances of the OP-XY splitting such control sets across various interface elements and screens. While designed logically and intuitively, the extra key presses required to get around can at times slow the workflow down.

Talking about things we miss, we also bid farewell to the OP-Z’s DMX light sequencing capabilities as well as its native support for controlling Unity visuals through videopaks. It’s a shame — these performance-oriented tidbits made a ton of sense and reduce gear clutter where it’s most unwanted: during live gigs.

Building up to a piece

Having had a lot of experience with the OP-Z before, it shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise that we felt right at home on the XY from the get-go. In fact, anyone who’s ever used a step sequencer should intuit quite a lot. Sixteen steps are directly accessible using a dedicated row of keys. Pressing an inactive step commits to it the last note (or chord) played. Pressing an active step deletes it. Holding a step down enables you to key in individual notes, tweak the note length, copy it, or precisely nudge its timing. Quite flexible!

Oh, and that row of sequencer keys features a snazzy color gradient (well, grayscale gradient to be precise) in sets of two that not only looks awesome, but lets you quickly visually subdivide the steps into groups of two, four and eight.

That’s only talking about a single bar, though. Unlike the OP-Z, the OP-XY supports patterns that are up to 4 bars long, bringing the total number of steps up to 64. The shiny new bar key is there to facilitate adding (or removing) bars and selecting which of the four bars’ steps show up on the sequencer key row.

Patterns can also be scaled, making each step last longer (or shorter). This is great for extended melodic phrases as it effectively allows for up to 64 bars (assuming you’re using the maximum 16x track scaling: remember, we used a similar trick to get longer patterns on the OP-Z too).

A powerful feature of the XY is its ability to work with custom pattern lengths. You’re in no way limited to multiples of 16. On top of that, there’s nothing stopping you from playing back multiple patterns of different lengths at the same time. If, for example, you punch in a 7-step pattern into one of your tracks and a 25-step one into another, the OP-XY will happily play back all the delightful ever-shifting mayhem. This feature was already present on the OP-Z, but nevertheless it never fails to impress, especially if you’re interested in more experimental beatmaking.

Patterns can be recorded live, which comes in handy for leads and solos that should sound more human, especially since quantization can be dialed down. Recording is also your gateway to more than one note per step. And to sweeten the deal, there’s no four-note-per-step limit here like on the OP-Z! Sadly, there isa new (and as far as we can tell, arbitrary) 120-note limit per pattern. Why? Just — why? (And yes, before you ask, chords count as multiple notes, meaning that a 4-voice chord counts as such. You’ll run out of space quickly — after only 30 chords — if you’re programming in rapid stabs or a similar chord-heavy texture.) Argh!

The OP-XY features a reworked song arrangement system. Each piece of music is represented by a project, and since the XY works with (mostly) MIDI data, there’s enough space to save hundreds of these. Each of the 16 tracks in a project has 9 pattern slots, and any combination of 16 patterns makes up a scene. Each project can hold up to 99 scenes, and up to 96 scenes can be chained into a song — of which any single project can hold 14, so arrange to your heart’s content. (And to the three scenes left out of your next grand 96-scene-long song — sorry, it was never meant to be.) Finally, a project also contains some configuration parameters defined across a couple of the XY’s menus.

For quick identification, every pattern comes with an adorably tiny “piano roll”–style preview visible in the arrange mode, as well as several other places in the UI. It’s extremely handy and helps de-clutter more complex projects.

This new setup, partially inspired by the EP-133, is a huge quality-of-life improvement and overall step in the right direction. Switching between patterns and scenes and editing them is quick and intuitive. For live use, it’s practically perfect. On the other hand, that pesky 120-note pattern limit does, well, limit how far you can take your ideas, especially since there are only nine patterns per track. Sure, this might not be a problem for typical four-on-the-floor beats, EDM tracks, VGM-inspired tunes — or even ambient tracks where time gets streeeeeetched. You also shouldn’t run into any issues when live jamming either (something that a groovebox is meant for, after all). But if you want to compose and refine complex pieces, chock-full of transitions and contrasting sections, you’ll simply run out of notes after a while.

Ah, but the OP-XY isn’t meant to be a workstation, as close as it gets to feeling like one at times. It shouldn’t be one. It’s a groovebox, so it’s fair to assume that all this is rather intentional (as grumbly as it makes us). With so much functionality packed in, every little limitation irks us all the more so. If there’s anyone out there taking notes, here’s our three-step guide to making us very happy. Step one: raise or, better yet, remove the note limit on patterns. You could stop right here and our grievances would effectively be resolved. Feeling yet more generous? Carry on — step two: raise the per-track pattern limit to 16 (or higher). Step three: seamless project chaining. Being able to utilize projects as sections of a larger piece and chain them together would turn the OP-XY into a pocketable DAW-like wonder, all while retaining its core groovebox design philosophy. One can but dream…

Oh, the things you’ll sequence

Don’t tell us you thought it was just notes? Come on — every groovebox worth its salt can do more than that, but the OP-XY takes it a few steps (pun intended) further. For starters, there are parameter locks, which can be placed on every step. While this is a common groovebox feature, the XY’s implementation is rather flexible, as any synth parameter can be automated — but so can any envelope, filter and LFO parameter (more on these later). Automation curves can also be edited (or perhaps better said, smoothed), though this is applied on a per-pattern basis. There’s no way to edit a singular curve.

Things get rather unique with step components, a feature inherited from the OP-Z. These sequencable little gizmos can be placed on any step to tweak or modify it in any of a number of ways (what an open-ended sentence — but it really is true). You want to randomize a step? There’s a component for that. You need some emergency portamento on a note or two? There’s a component for that. You want a step to repeat, say, 7 times before moving on to the next? Say it with us: there’s a component for that!

And while all of these are powerful, undoubtedly zany and just plain fun to fiddle around with, it’s the final four components: jump, parameter, component and trig that are signature features of the OP-XY’s entire sequencing system. At its core, jump does what it says on the tin — once triggered, it causes the sequencer to hop over to another step. Jump also offers some niche options: there’s stuff like going back a single step (one step forward, one step back, eh?) or jumping to the same step that triggered the jump in the first place, resulting in an endless loop.

But the real magic comes in the form of parameter, component and trig. In a nutshell, these let the sequencer skip parameter locks, other step components or note triggers based on the number of passes the sequencer makes through the step. You could, for example, have a note trigger every second pass, while the associated parameter locks trigger every third time (naturally, independent of whether the note actually fires or not). For fun, why not have a pulse component trigger every fourth pass, repeating a step multiple times. Combine all of these together and it’s pretty clear how much sequencing chaos can happen in a rather short amount of time. If things get too out of hand for your liking, our old friend jump can be used to re-sync the track back by performing an automated jump that compensates for repeated (or skipped) steps caused by any previous step components.

Oh, but we’re not done with sequencing shenanigans yet. Remember the eight auxiliary tracks? We’ll cover what they have to offer a little bit later, but for now, let’s just mention that the XY’s sequencer doesn’t discriminate. It’ll happily sequence just about anything. Say you want to set some parameter locks for one of your effects’ parameters, automate transposition, sequence pocket operator-style punch-in effects or control a modular bit of gear while also sending MIDI data out of the OP-XY’s USB-C port. It’s all possible thanks to the unified sequencing workflow that extends way past the eight instrument tracks.

Modes and modules

With the sequencer covered, it’s time to take a look at the logic and organization behind the UI. This is where things finally make a more radical departure from the OP-Z paradigm. Since the XY has the luxury of having a screen, we’re treated to a UI that’s been re-engineered from the ground up.

…well, maybe re-engineered is too strong a word (a word and a half?), as many elements got snatched over from the OP-1, but you get the point. Just like on that device, the OP-XY’s interface is now compartmentalized into four main modes: instrument, auxiliary, arrange and mix.

Quite akin to the OP-1’s track buttons are the OP-XY’s module keys, down to the numbers printed on them. On the XY, these can be used to swap between various screens in a selected mode, such as accessing a synth’s envelope and LFO settings or the master EQ and compressor in mix mode.

While talking about the song-building workflow, we’ve already covered most there is to say about arrange mode. Its handy interface provides nifty pattern management tools, including the ability to create new or copy/paste and delete existing ones. The song editor, part of arrange mode, is accessed by shift-clicking the arrange key.

Mix mode is similarly simple. Its (elegant, dare we say) interface allows for easy access to all key parameters of the OP-XY’s tracks, with FX sends, volume, panning, muting and soloing all directly controlled by the four main encoders. There’s also a master equalizer, a saturator (essentially a compressor/drive/limiter combo) and a master volume control, all accessible using the four module keys.

Finally, there’s instrument and auxiliary mode. This is where the grunt of the work happens, with each mode providing access to the sequencing underbelly of its eight corresponding tracks. Instrument mode is also where the sound design magic happens (ooh, spoiler alert). It’s perhaps the most OP-1–esque of the lot. Across all eight tracks, module keys are used to access the synth/sampling engine itself, a pair of envelopes, a filter and an LFO. Auxiliary mode is similar, though with many tracks featuring their own custom modules, it feels less streamlined as a whole. As a little side note, we noticed a few bugged-out modular vestigial remains: what’s an LFO doing on the CV track?

Modes and modules aside, some functionality lives within its own set of dedicated interfaces. As there’s no official collective name for these, we’ll keep it simple and call them menus (not very inspired, we know). The project management menu lets you create, save, rename and configure projects (finally, there’s an option for choosing time signatures — hooray). The metronome menu offers a quick way to change project tempo and metronome settings as well as groove type and amount. The comms menu is expansive, letting you configure the OP-XY’s multi-out, manage wireless settings and MIDI devices (wired and wireless), use the XY as a MIDI controller (at only $95 per key it’s a steal!) and access the general system settings page. It’s surprising to see such granular control on a teenage engineering device. We’re not complaining though — simply commenting as it’s a (welcome) change of pace.

But ah, so far this is mostly mundane device and project setup stuff. The final two menus are likely of most musical interest — one housing the OP-XY’s powerful sampling features and the other (with its rather extravagant players name) is a basic MIDI manipulation toolkit: an arpeggiator, flexible chord generator and drone mode group neatly grouped together.

The OP-XY hardware

By now, you probably already have a more-than-solid idea of what goes into making an OP-XY. Start with an OP-1 field chassis, keep the speaker, screen and encoders, tweak the keyboard layout and replace the switches with a more tactile-feeling set. One color swap later, you’ve more or less got the OP-XY. For OP-Z users, most of these borrowed features alone will be a big upgrade.

Here’s what we mean by that cheeky most: with the encoders being virtually the same as the OP-1 field’s, we do say farewell to the OP-Z’s incredible low-friction hall effect encoder design. Those are the stuff that dreams are made of — smooth, responsive and endlessly satisfying to use. XY’s encoders aren’t half bad (in fact, they feel great), don’t get us wrong, but they aren’t anything too special.

Come to think of it, it’s rather intriguing that we’ve still got the exact same 480 x 220 IPS color display. The XY’s interface is all monochrome, with sparing use of red to highlight that there’s some sort of recording going on. It’s a sleek look, but perhaps one that’d look even more striking on an OLED panel — even a monochrome one.

The chassis, though — oh, the chassis. If you’ve ever held an OP-1 field unit, you know exactly what we’re about to say. It just feels so incredibly premium. The black anodized finish is also beautiful, though it’s likely easier to scuff than the natural silver of the OP-1. We’ve had luck and haven’t picked up any unsightly marks so far, but only time will tell how durable the XY’s beauty is.

The suspicious black rubber pill on the XY’s front side is its pitch bend wheel-pad-thing. Another bit of homage to the OP-Z, the pitch bend pad has been significantly enlarged, and while it still seems to utilize piezoelectric pressure sensing tech, it’s a lot more sensitive and reliable than the old implementation.

There’s a neat array of IO options on the OP-XY’s right-hand side. No modern device is complete without the customary USB-C port for charging and data transfer (and naturally, with both MIDI-over-USB and USB audio support). Right next to it are four 3.5 mm jacks for connecting outboard gear or routing audio in and out of the device. The main line/headphone output curiously supports headset microphones (for M-1 compatibility, perhaps). We generally use higher-impedance headphones in the studio, and were pretty happy with the way our 250-ohm cans sounded straight from the XY — so you shouldn’t run into any issues either.

Perhaps the most intriguing of the lot is the multi-out, a configurable 3.5 mm output which is capable of handling MIDI, CV, modular sync and audio signals — all through one single connector that’s easily configurable from the comms menu.

This IO setup integrates functionality provided to the OP-Z by its optional expansion modules and interface, itself a feature that the OP-XY lost. Of the three modules released for the older machine, only the rumble module’s features didn’t make it over, something more than made up for by the better speaker with its bass vent (though — we have to say — a better speaker is nowhere near as fun as feeling your entire desk go bzzzt with every low note).

Under the hood, the XY sports all-new guts. A dual-core CPU (reportedly an Analog Devices Blackfin model, meaning we’ve got some DSP power, too) paired with 512 MB of RAM and 8 GB of user storage marks a major step up in bulk computing power. There’s no official info on the signal chain, but it doesn’t seem likely that teenage engineering took a step back from the 32-bit/44.1 KHz spec of the OP-1 field. Despite that, the XY still samples at 16-bit/44.1 KHz, the same as the OP-Z. We’re not sold that this is the best this beefy new hardware can do — perhaps a future software update can address this?

The battery life is great. teenage engineering claims you can get 16 hours from a single charge, and this roughly checks out. Assuming that the OP-XY and OP-1 field share the battery model (and they likely do), the latter’s longer, 24-hour battery life could be easily explained by its lower-power hardware.

With the new, clickier keyboard redesign, it would’ve been nice to see teenage engineering bring over the pressure-sensitive pads from the EP-133. Instead, it seems that velocity on the OP-XY is handled in much the same way as on the OP-1 field: using an accelerometer. It’s a bit of a missed opportunity, but nothing worth whining about too much. Overall, we’re dealing with some great new hardware that’s a major upgrade from the OP-Z, and in some ways, the OP-1 field too.

Sound design on the OP-XY: a deeper dive

…because what good is a groovebox if its bleeps and bloops don’t inspire you? Thankfully, this is where the OP-XY manages to run laps around its predecessor — all while said predecessor already had a wide and lush sound palette on offer. Admittedly, the OP-XY has less synth engines than the OP-Z. But with four tweakable parameters instead of two — and a dedicated filter with four parameters of its own — the XY manages to cover significantly more sonic territory.

In the OP-XY paradigm (and OP-Z), a track holds both MIDI data and all the patch settings, not unlike a DAW. To be a tad more precise, each of a track’s nine patterns holds its own patch (and mixer) data, making it possible to quickly swap between sounds on a single track. This capability is especially powerful when used in conjunction with auxiliary tracks as it opens the doors to unexpectedly flexible automation of settings that parameter locks don’t cover.

While talking about the modules, and more specifically, the modules that make up instrument mode, we’ve covered the basics of what makes an OP-XY patch. The signal path starts with the synth engine, which provides the basis of a patch’s sound. After that, a pair of envelopes help further sculpt the sound — one controlling the amp and one controlling the filter. The filter lives in its own dedicated module and thus offers a solid degree of control and some nice character to boot. Finally, there’s the LFO, which can modulate pretty much any parameter of the synth engine, the envelopes, or the filter. (And in some modes, the LFO can use things like the XY’s accelerometer as its mod source, making it function less like an LFO and more like a very simple mod matrix).

The synth engines

Let’s take a look at core noisemakers: the synth engines themselves. If you exclude the three sample engines and the external MIDI engine (this one lets you turn any instrument track into an extra MIDI track), there’s a total of 8 to choose from.

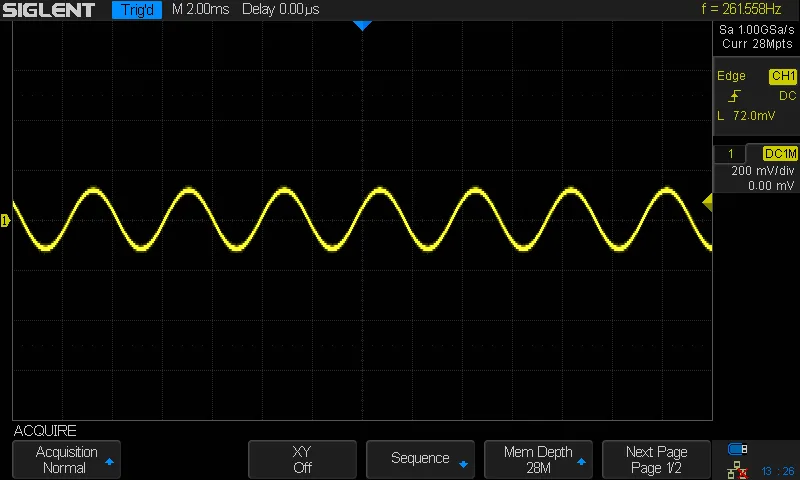

The simplest of the lot is simply named simple — things sometimes just make sense. It’s a virtual analog engine that provides you with a basic saw waveform that can be morphed into a square wave using P1 (for clarity, we’ll be referring to the four encoders as P1-P4, short for parameter). P2 tweaks waveform pulse width. Simple white noise can be added with P3 while P4 creates stereo width by applying a stereo phaser to the signal.

There’s nothing too crazy going on here, but paired with the flexible filter (which we’ll get to soon), there’s quite a range of obtainable utilitarian sounds that work rather well for basslines, leads and keys. Not really important to the sound, but the graphics are rather whimsical and cute on this one.

Next on our list is prism. It’s a no-fuss dual-oscillator synth engine. P1 sets the shape of both of prism’s oscillators, going from a relatively clean sawtooth to a square. Near the end of its range, P1 seems to asymmetrically tweak pulse width, leading to a more prominent second harmonic. P2 sets the frequency ratio between the two oscillators, jumping in steps of fifths and fourths. P3 detunes the second oscillator which makes for a lusher sound, but doesn’t let you dial in any extra intervals between the two oscillators due to the limited detune range.

As there’s no modulation here, detune doesn’t do much but fatten up the sound — and P4’s stereo option helps take this further with a similar stereo phaser effect we’ve seen in the simple engine. In fact, prism is a lot like simple’s dual-oscillator equivalent, an excellent basis for a lot of the same things — simple, staple leads and basses.

Another seemingly utilitarian sound engine, wavetable, is not quite what it initially seems. P1 selects one of the nine wavetables (which are, truth to be told, pretty intriguing) and P2 smoothly scrolls through it, selecting a shape. Similar to the OP-1’s Dr. Wave engine, the display acts as a rough waveform visualizer. It doesn’t religiously follow the actual oscilloscope view, but — in a weird way — it makes intuitive sense.

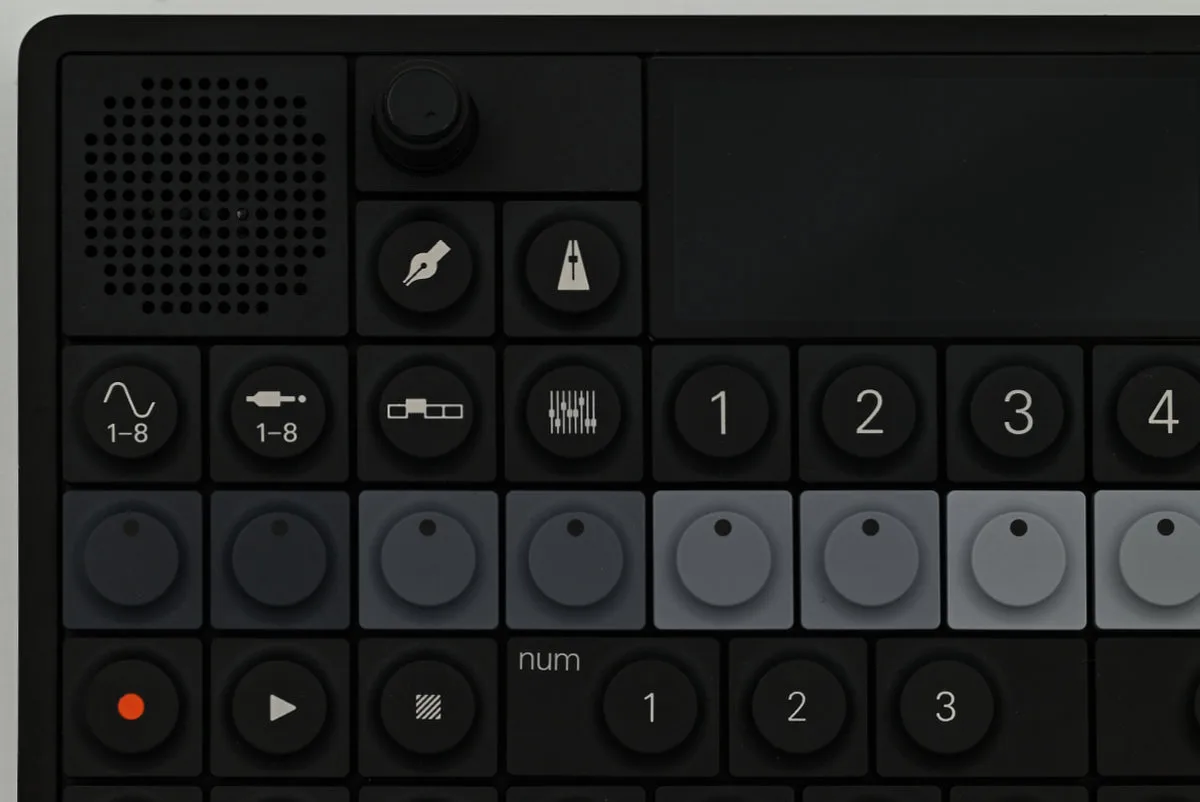

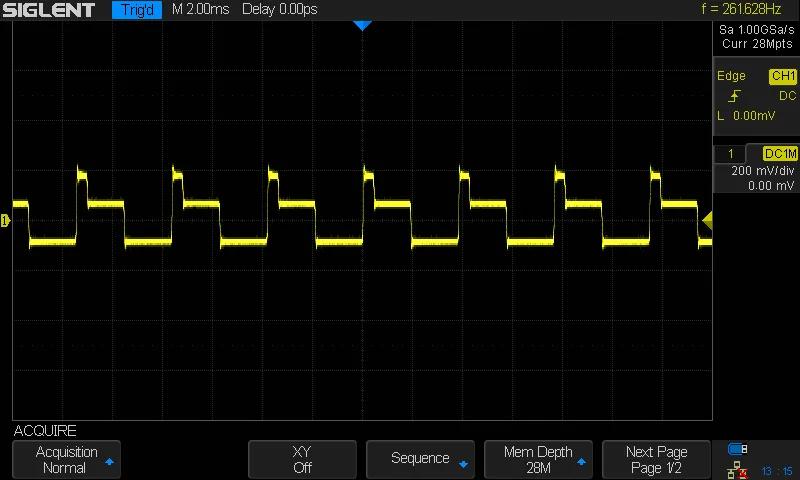

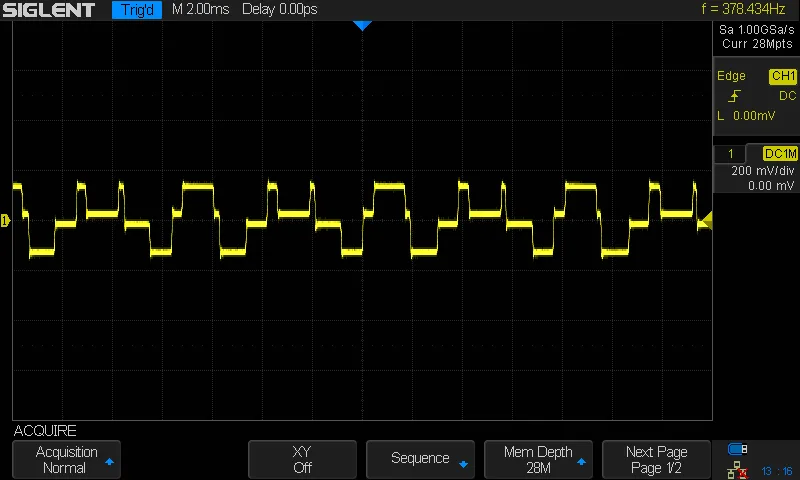

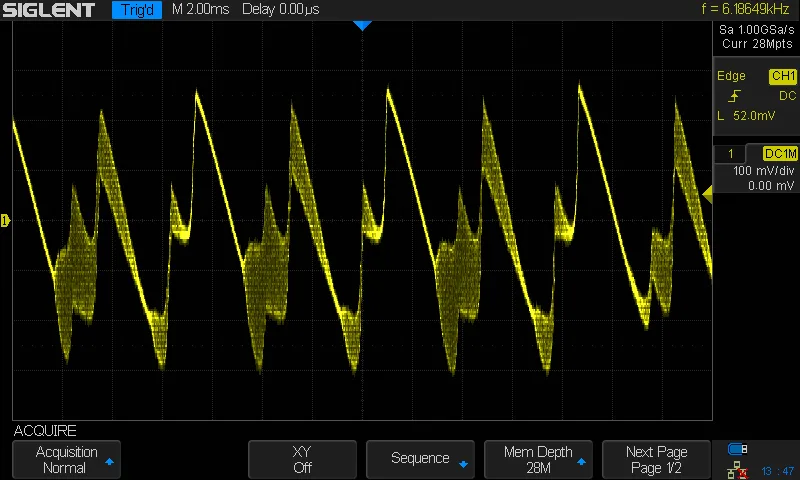

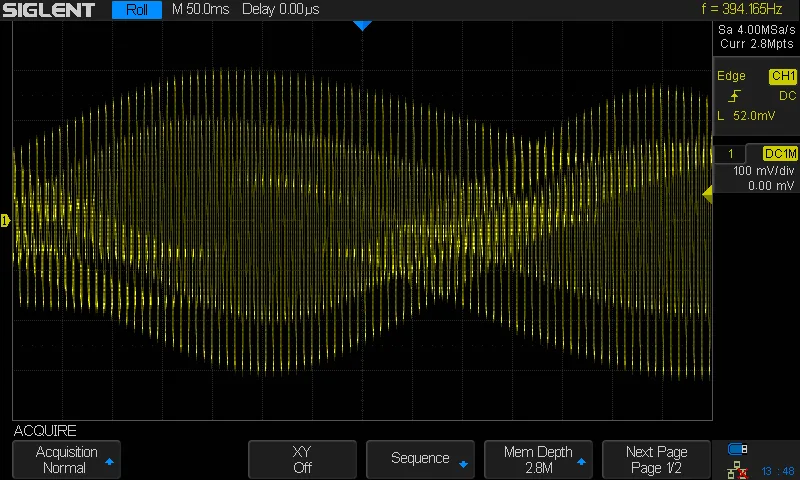

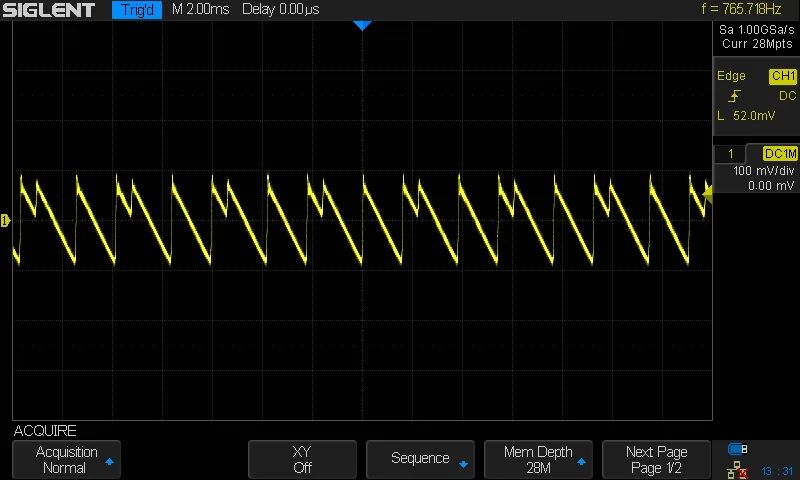

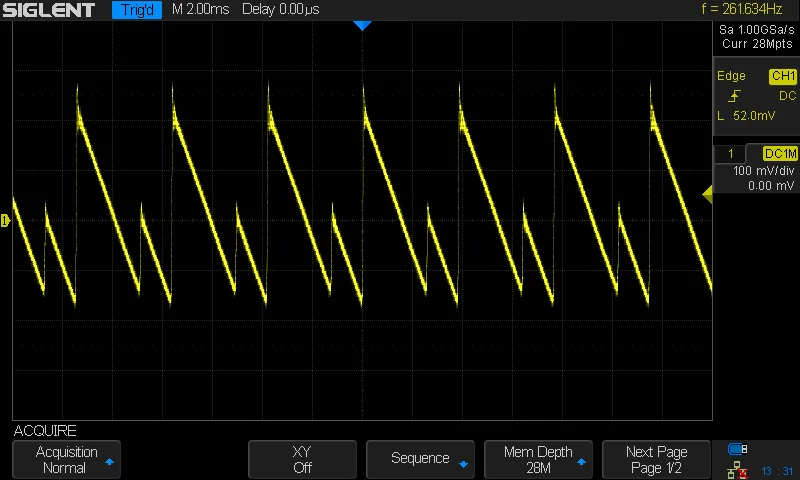

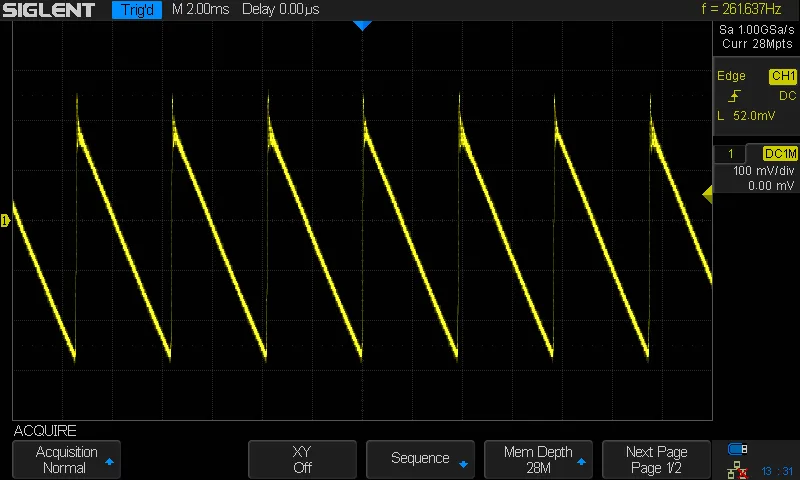

That is, until graphics display a — wait, what — waveform going back in time? See, things get a lot more interesting once you touch P3 and P4. At first glance (and listen), it appears that P3 does little more than (yet again) affect pulse width, but that’s not all. An audible overtone instability also hints that there’s likely some FM going on here. Turning P4 seems to only confirm our suspicion, with a full range of characteristic distorted and clanging bell-like noises attainable.

So, here’s our take on what’s actually going on here. We’ve got a simple two-operator FM setup. P3 seems to control the FM amount. With P4 set to 0, the second oscillator (operator?) is tuned to the same pitch as oscillator one. And to all the analysis purists out there — yes, it’s likely that it’s actually detuned a few cents from the get-go in order to produce a more audible result. This would explain the sound getting lusher and lusher the more P3 gets turned up even with P4 untouched. And P4 seems to simply detune the second oscillator, which makes all the wonderful FM things happen — it brings out all the weird and wonky inharmonic partials.

Wavetable isn’t the OP-XY’s only FM-based synth. Axis is an achingly musical engine that’s at its best when used for thick, layered pads. With a mellow FM algorithm (which once again sounds like it’s only got two operators) getting nice-sounding results is really easy. The magic is in the lush, evolving waveform that the operators use. P1 controls a low-pass filter with an interesting resonance profile, P2 controls the second operator tuning, with it starting an octave below the first and smoothly sweeping up an octave to match the first with the encoder set halfway. Past this point, the second operator covers a span of five octaves in characteristic fifth-fourth leaps. P3 controls the operators’ wave shape, tightening up the transients and morphing the complex waveform’s base between a sawtooth and triangle wave. Finally, P4 adds a lush, string-like tremolo effect.

Axis’s graphics are wonderful. This is largely subjective, but they’re our favorite of the bunch. Something about all the little 3D cubes smoothly moving around makes using this engine feel oh-so-satisfying…

Two of the OP-XY’s engines emulate other instruments: the epiano and organ. The former starts with a sine wave. P1 seems to modulate the sine with a saw/square wave. To our ears, it seems that this knob not only controls modulation amount but also tweaks the modulator wave’s shape a little.

P2 affects the carrier, with the sine slowly morphing into a triangle-like wave with more and more pronounced peaks past the twelve o’clock position (essentially, what we’re doing is going from a pure fundamental and increasing the presence of its first few partials). P3 highlights a note’s attack by mixing in a fast-decaying and higher-pitched second oscillator. This leads to a much punchier presence and a lot more immediate overtone content that cuts through mixes.

Finally, P4 is a demodulation timer of sorts. When set to 0, a note remains stationary for as long as it’s held (unless, of course, there’s some attack tweaking with P3). As P4 gets turned up, it takes less and less time for the note to decay back from its modulated state into a pure carrier sound. In our case, that’s the pure sine or triangle wave. At very short decay times, the notes get a noticeable plucky character. According to teenage engineering, this is supposed to model an electric piano’s tines — it’s an interesting way to go about this (we’d have expected more of what P3 does, really), but it’s effective and allows for some non-EP character out of the engine. It’s surprisingly good for leads and basses, and not just keys!

And we’ll be the first to admit — it’s possible that our analysis here is extremely off. It’s really hard to piece together what this engine actually does, especially when what most parameters do is make the sound brighter, and the vague official docs don’t help much.

On the other hand, organ seems simpler. Built to emulate both classical pipe organs and electric jazz-style ones, its P1 setting selects an organ type and registration. P2, dubbed bass in the manual, does indeed add a sub-oscillator in some modes, yet mixes in some higher frequencies in others. Generally speaking, it adds harmonic content — and in some cases even brings detune to the mix (definitely pointing towards more than one oscillator being present). P3 and P4 are interlinked and control tremolo depth and rate, respectively. The OP-Z’s organ engine had some FM magic baked in so we don’t doubt for a bit that the XY’s version also has some of the funkiness going on. All we’ll say is that changing organ types does sound suspiciously like scrolling through FM algorithms — which would also explain P2’s intriguing behavior.

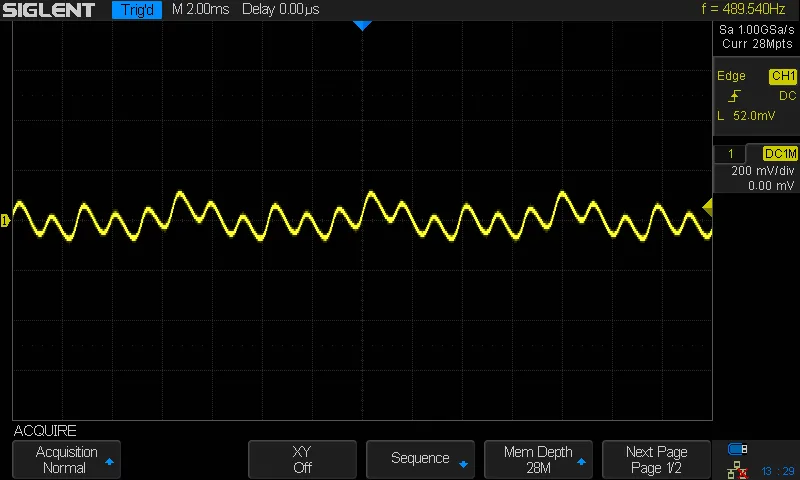

Hardsync is a heavy-punching lead synth with a noisy, digital signature. It starts with a pair of synced saw oscillators. P1 controls the detune between them over a span of three octaves. As the name suggests, the two are hard-synced together, which defines the synth’s main timbre. P2, named sub in the interface, controls a sub-oscillator. Curiously, this sub-oscillator is actually tuned to the same frequency as the main oscillators. Due to the nature of hard-syncing, this often results in a sub-oscillator type sound (as the synced oscillator pair jumps up an octave when the leader oscillator’s frequency doubles the follower’s). Where this is not the case, the sub-oscillator simply fattens up the patch by doubling down on the fundamental frequency.

P3 adds white noise to the mix, and P4 (curiously) controls a high-pass filter (an interesting combination with the noise). This additionally drives home the tinny, digital sound. It’s definitely interesting, and while perhaps not our favorite, it does accomplish what it sets out to — it’s great for those anthemic leads and stabby keys.

Finally, dissolve. It’s arguably the most fun of the OP-XY’s engines, but trying to tackle it scares us. Essentially, dissolve performs multiple types of modulations using noise as a modulation source — and a pair of sine oscillators as carriers. P1 mixes in filtered noise and sets the intensity (and rate) of a soft, randomized pitch modulation applied to both of the oscillators. The next two encoders, P2 and P3, control AM and FM algorithms that further change the signal, yet again using the noise as a modulation source. P4 is, thankfully, pretty simple. It allows you to detune the two base sine oscillators up to slightly less than a minor second apart, adding more lushness and creating a very pronounced, characteristic beating due to out-of-phase interactions between the two.

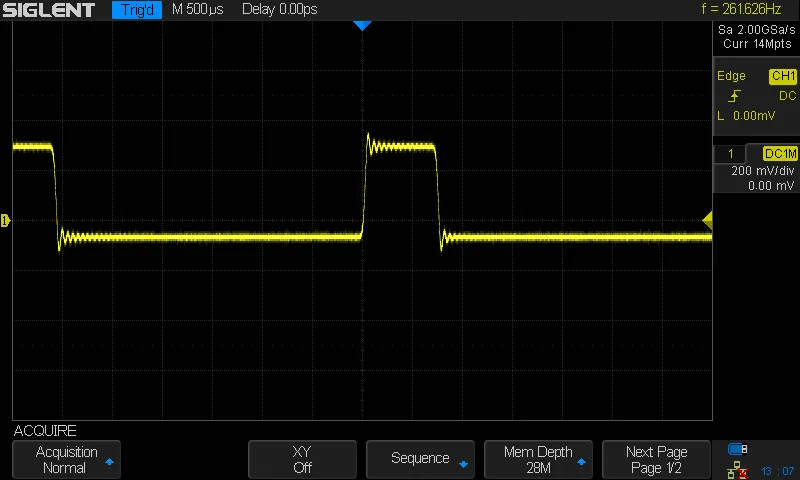

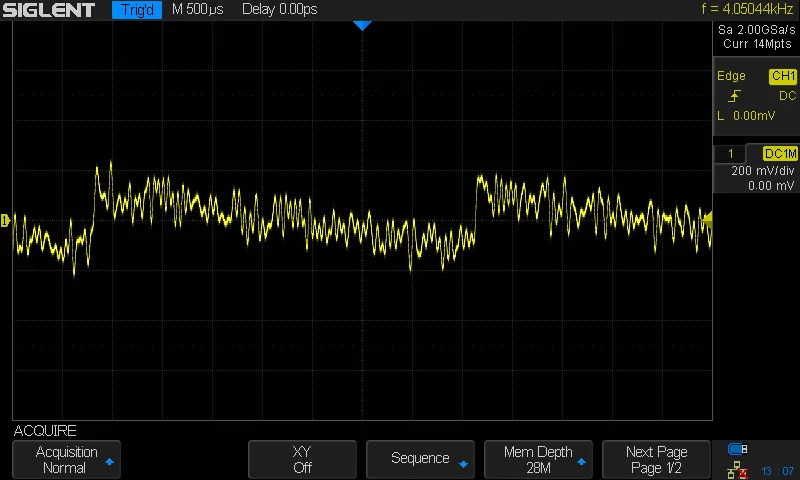

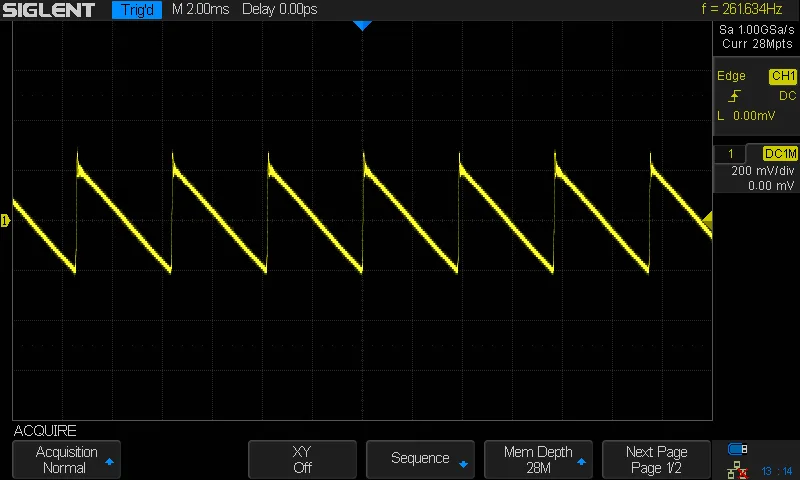

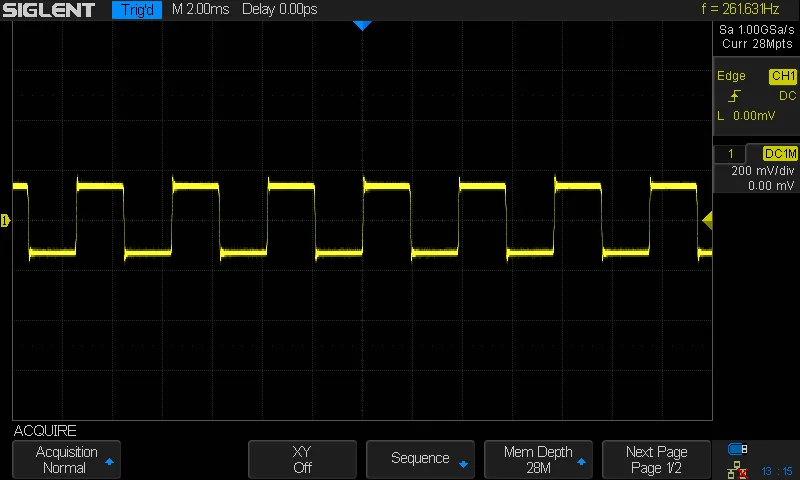

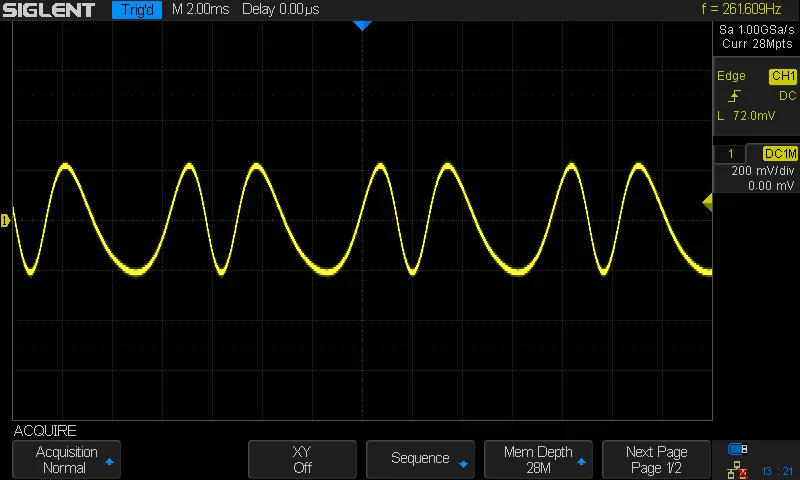

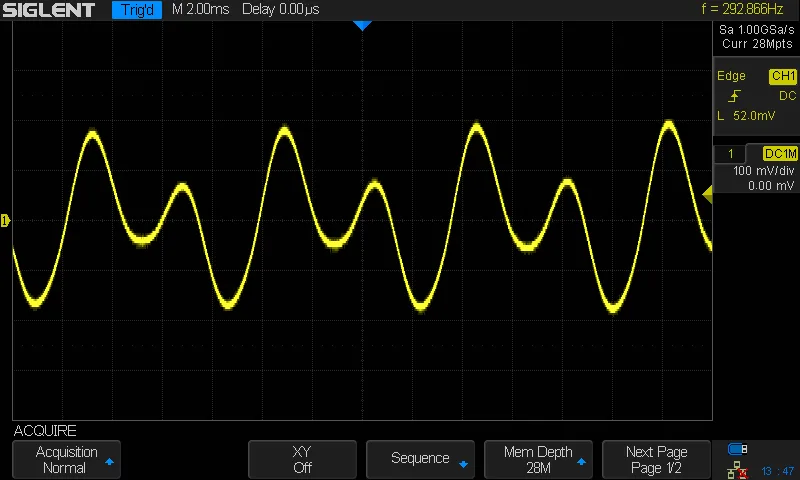

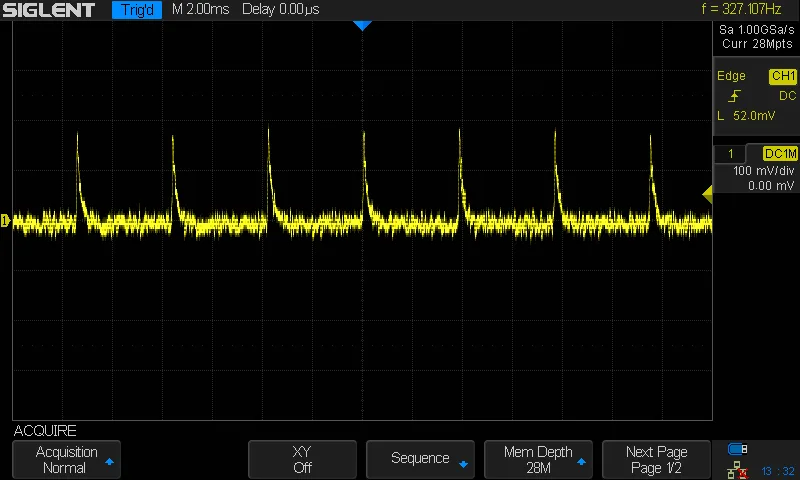

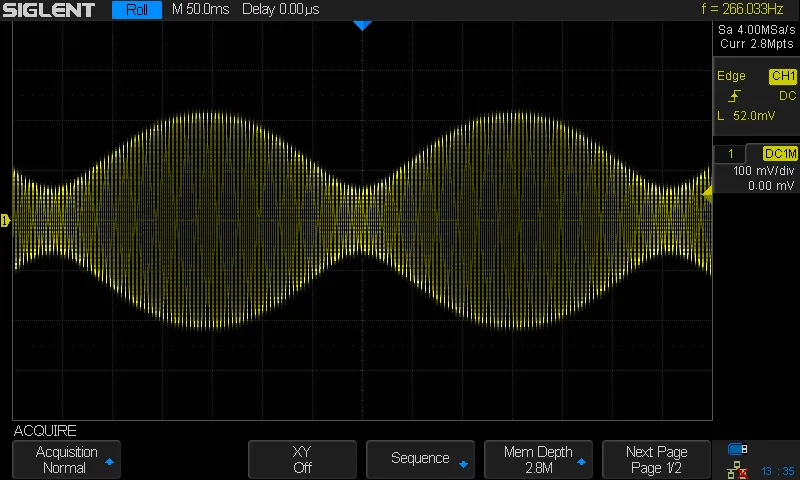

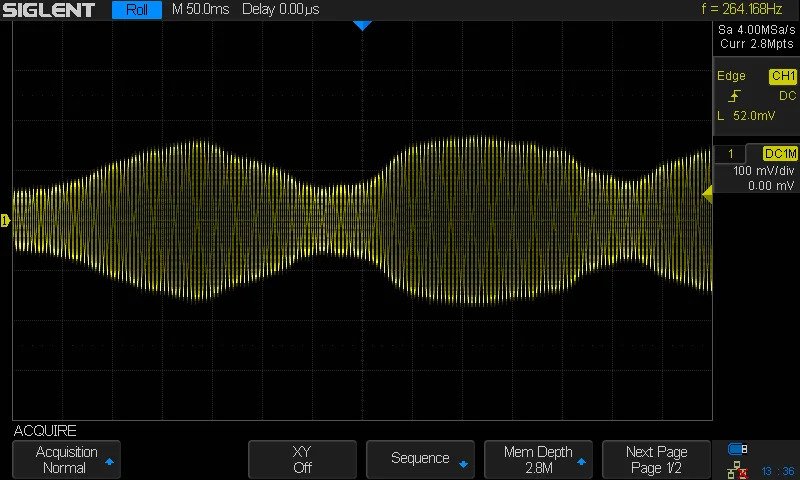

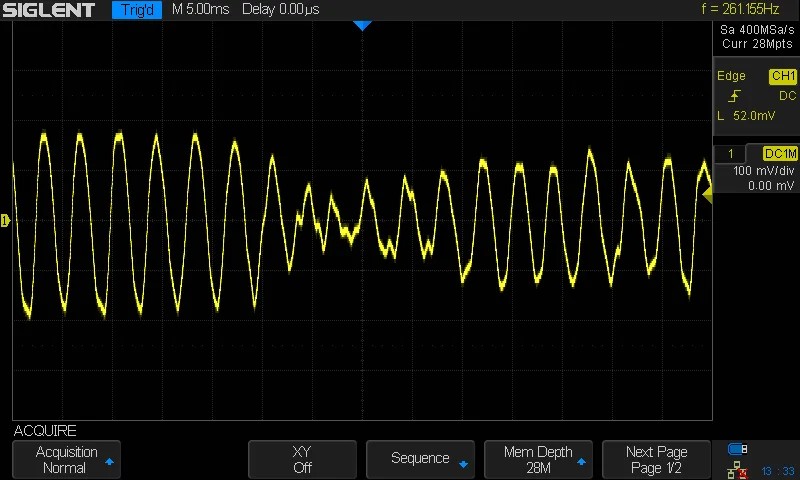

Because there’s simply so much stuff going on, it’s hard to single out out the exact inner workings of the engine. Broadly speaking, P1 and P4 work together to set up an evolving AM-like sound, with P4’s detune providing the overall wave shape and P1’s noise and randomized detune significantly affecting it. This modulation happens over longer time spans and is prominently audible as a general instability in volume. P2 and P3, in contrast, provide more localized modulation. It’s only visible by zooming in down to the waveform level on an oscilloscope, though musically, the differences it causes in the harmonic makeup are more than audible and greatly affect timbre.

Dissolve is surprisingly musical for a noise-based engine and thus makes for a great all-rounder thanks to its evolving tone quality. It sounds great for keys, leads and — this shouldn’t be a surprise — complex, evolving pads. It’s a treat!

We’ve said this already, but having four instead of two parameters supercharges the OP-XY’s sonic capabilities. With more conservative synth engine designs at its core, we can’t but feel that, compared to the OP-Z, it simply offers more immediately usable, bread-and-butter sounds. It’s hard to get an XY patch to sound bad or thin, no matter how you twist its knobs — a feat that the Z definitely didn’t always live up to. On top of that, the dorky scramble feature is great for when you need some quick inspiration. By jumbling around the parameters randomly it can provide you with a more interesting starting point than the default all-pots-to-the-left.

This does mean that the dark arts of experimental sound design can’t be pushed to the same extremes as on the Z. (Anyone remember its crazy digital engine?) Utility or experimentation? It’s a choice you’ll have to make.

Sampling on the OP-XY

The OP-XY has three samplers: a standard, run-of-the-mill one-shot melodic sampler; a matching drum sampler and a multi-sampler engine. Collectively, these make up one of the finest sampling setups we’ve seen on a portable music-making box — some of the competition also coming from teenage engineering. The one-shot sampler has been yoinked straight from the OP-1 field, with the same immediate workflow (hold down a key and make some noise — it’ll get automagically mapped across the keyboard) and the same set of tools for editing a sample’s start, end and loop points, tuning, playback direction, applying crossfades and gain control. Pushing down an encoder zooms in on the waveform view for mode precise control. Though, admittedly, the OP-1 field does zoom in quite a bit more, making it a lot easier to make smooth pads without relying as much on the crossfade.

The drum sampler is similar, with the same basic sampling workflow — with the notable exception of every key holding its own, different sample. The workflow is, thus, a little bit different: press a key down to select it and hit the record button to start sampling. Naturally, there’s also a tweaked set of tools more suited for percussion and sound effects. In addition to start and end points, you can tune the sample, switch it between several play modes, including support for choke groups, set playback direction, panning, crossfading and gain.

But the real star of the show is the multi-sampler. The way it works is quite similar to the rest of the lineup (and it even offers all the same tools as the one-shot sampler), but allows you to distribute up to 24 different samples across the playable range for a much more natural sound. There’s nothing complicated about the workflow, as it’s quite similar to the drum sampler. Choose a key, hit record; rinse and repeat for your instrument’s various registers. The OP-XY’s multi-sampler always pitches sounds down, meaning that sample zones get automatically created as you work your way through the octaves.

The OP-XY stores all your sample recordings regardless of whether you’re actively using them in a patch or not. All previously recorded samples can easily be recalled (a step in the right direction; compare this to the OP-1 field, which only stores samples as parts of a preset), but the file management system leaves a lot to be desired. Unlike patches and projects, sample recordings can’t be renamed nor deleted straight from the device, requiring you to use a computer to sift through your recordings and clean out the clutter. Even worse, with auto-generated names like unnamed-b2-3, it’s rather difficult to get around once you’ve got more than a few files in your sample library.

…and getting there won’t take you long! Within a few days, our own OP-XY was already overloaded with various instrument samples and… erm… vocalizations, and was in dire need of a cleanup.Even when you don’t have one of the sample engines loaded, it’s just so easy to grab new samples thanks to that dedicated sampler button, no matter where in the interface you are. These recordings are then saved alongside your other samples for future chopping and use — provided you can find them in the endless drop-down list. It’s a shame that the thing holding the whole sampling workflow back is the lackluster file management system. This shouldn’t be hard to address in a future update. Please, the samplers are awesome, but give us the tools to tame our ever-growing sample lists.

Envelopes and filters

With a dual-envelope design and a fully-tweakable filter, the OP-XY has teenage engineering’s most robust synthesis setup. The ADSR envelopes live in their own little module. One controls the VCA and the other the VCF. Having separate envelopes is a godsend for sound design — and is surprisingly a feature absent on a number of grooveboxes.

Where the OP-Z’s filter was strictly low-pass, the OP-XY actually offers four types: low-pass, ladder, SVF and high-pass. The first three represent various flavors and characters of low-pass, which is nice but perhaps a bit of a missed opportunity with the SVF filter — how wonderful it would have been to have manual access to all of the filters outputs, perhaps with a little mixing stage. Imagine all the sweeps and swoops…

The filter’s P1-P4 control, in order, the cutoff frequency, resonance, envelope amount and key tracking. Pushing down P1 is a shortcut for switching filter types (which does sometimes get in the way, but is nevertheless handy for quickly auditioning sounds).

Very off topic, but P4, when pressed, brings up a little reminder that it controls key tracking. No other element in the entire interface does this — not that we’ve seen. Just felt like this is an intriguing thing to point out.

The filter sounds good and smooth. A tad (expectedly) digital in its basic low- and high-pass modes, yet often surprisingly plush, especially at higher resonance settings in the ladder mode. SVF has a similar character, though to our ears it’s not as special. When it comes to things like these, the more the merrier — it’d be real nice if we were to see some more filter types added further down the road in a software update. A dedicated band-pass or notch option would be nice, though the former can be approximated when using engines that come with their own filter (like axis; and yes, to clarify, engines with their own dedicated filter have it operate completely independently from the main filter, meaning you get two at your disposal).

But wait, there’s more. The OP-XY has a special little patch settings menu accessible by shift-pressing the synth key. Here’s where you’ll find things like custom tuning options, transposition, portamento settings, a performance-oriented modulation matrix of sorts (which can use the modwheel, pitch bend, aftertouch and velocity as a modulation source) as well as — and this is why we’re mentioning this here — a hidden sneaky high-pass filter. There’s no dedicated resonance control and it’s pretty rudimentary, but having it is nice for emulating band-pass sounds with engines that don’t feature their own filters, or simply for clearing up the lows on an otherwise brooding and muddy patch.

Effects, sends, signal path and the LFO

The XY features two effect busses, each with its own dedicated auxiliary track. We’ve talked a little about the benefits of having the full sequencing capabilities on these: great for automating FX parameters and all that. On top of that, every FX track comes with its own band-pass filter (pretty flexible, as it allows for manual control of both its low-pass and high-pass cutoff frequency) and LFO for even more control. But we haven’t explored the effects themselves at all.

There’s six to choose from, all with rather no-nonsense names: chorus, delay, dist, lofi, phaser and reverb. The effect parameters are also pretty straightforward: you’ve got all the standard rate, depth, feedback, dry/wet mix and modulation knobs. It’s a stark difference to the madness that… well, whatever CWO was on the OP-1. And while much easier to grasp, we miss the whimsy. On the OP-Z, effects only have two parameters, much like its synth engines, so the more streamlined approach made sense. The two extra parameters on the XY could have afforded more room for creativity. Still, we can’t complain too much. All six effects sound good, really good even — and allow for some polished-sounding final results.

Going a bit off-topic again: here’s a minor UI inconsistency that we’ve stumbled upon while playing around with the effects. When selecting a synth engine or filter type, the key combo is always shift + M1 (that denotes the first module button that sits below the display, not the first track button). For choosing a specific patch, the menu can be accessed using shift + corresponding-track-number-button. For example, in case of the second track, that would be shift + 2, but that’s for patches, not engines! So why, then, does selecting an effect type use the latter combo instead? It makes no sense. Minor gripe, and even easier to fix.

Effect sends are managed on a per-track basis (there’s no per-track effects, though, like on the OP-1), with each of the eight instrument (and some of the auxiliary) tracks having a separate send level to both of the effect tracks. These can be controlled from the tracks themselves, or in a more centralized fashion, using the effect tracks’ custom routing module. The first effect track can also send its own output into the second one for some snazzy effect chaining.

Now that we’ve touched upon the way the XY handles some of its sends (and also given the fact that we’ve put it right there in the section heading), it might be a good idea to take a look at the rest, too. All of the tracks, instrument and auxiliary, are routed into the main mixer (a part of mix mode — if you recall our musings from earlier) where they can be mixed and panned. The mixer’s main interface provides a redundant set of effect send controls which is pretty handy when it comes to adjusting the sound just the way you want it.

Each of the XY’s tracks also has dedicated sends to the multi-out, allowing a different sub-mix to get sent out, as well as to the internal tape track. The former is vital when using an external effect processor — and the latter allows for subtler tape effects (we’ll get to this in a bit).

With all the levels set, the final step for the audio is through mix mode’s three-band equalizer, OP-1–esque saturator and finally, a master volume knob. This is where the XY’s crunchy sound magic comes to life, as these final steps of the signal chain truly impart their character. Taking the time to learn how these work is well worth it — after all, the OP-1’s drive and release parameters found on its master volume screen are where a lot of the magic happens.

Finally, let’s take a look at the LFO. Just like on the OP-1, each patch has its own LFO stashed away in the fourth module slot. There are four types on offer here: element, random, tremolo and value. Element can use several different sources (including the XY’s on-board accelerometer, microphone, amp envelope and the overall sound) to modulate any of the engine, envelope, filter or amp parameters (the latter’s got three: volume, pitch and pan). It’s like a very simple mod matrix! And if you remember the patch settings menu from a few paragraphs ago, with its performance modulation options, you should see how you’ve got a pretty flexible toolkit for making your sounds evolve and respond.

Random uses a random LFO to modulate engine, envelope or filter parameters. The LFO can run either synced to note triggers or freely, and comes with a simple envelope of its own that modulates the LFO amount over time. Value is similar, though it drops the envelope functionality in favor of a more traditional LFO with four selectable waveforms (sine, square, ramp and two sawtooth types).

Finally, tremolo applies both volume and pitch tremolo to the sound. With four types to choose between (sine, sawtooth, square and pulse) and the same envelope setup as random, it’s a versatile sound design tool to have.

A few demo tracks…

It would be no fun to have talked this much about all the various engines and filters and what not without giving some audio samples too. Well, here are some that we’ve cooked up.

This is a little jam-type track that uses the OP-XY as the brains of the operation, sending out MIDI data to an Arturia MiniBrute 2 and a Korg Minilogue xd, with some parts performed live on the OP-XY itself and a Waldorf STVC.

The following bit of silliness is a product of our first few hours with the OP-XY. Using a lot of the default patches and playing around with the sequencer we tried to create a track that sounds a lot like something you’d create using an OP-Z. Composed and mixed right on the XY.

Heh, this is our favorite of the review byproducts. It’s a short little VGM-inspired track that, just like the previous one, is all OP-XY.

Finally, here’s a track that uses several of our own patches and the OP-XY’s refelt piano multi-sampler preset for a groovy little jam. It’s all OP-XY, though a MIDI controller was used for the upright piano solo.

Auxiliary tracks

Whew, let’s hop on over to the other side. The eight auxiliary tracks might not be as inherently fun as the instrument ones, but they’re still integral to the workflow. In order, we’ve got the Brain, punch-in fx, external MIDI, external CV, external audio, tape and two effect tracks (we’ve already covered these last two just a second ago, so we’ll skip them).

The Brain is a transposition system, though a pretty clever one. By using some fancy algorithm magic, it analyzes your tracks and determines a key center, be it a regular major or minor scale or something more modal. And it generally gets things right (and if it doesn’t, you can manually punch in your key). Once you’re in the Brain track, pressing a key changes the root note and transposes everything (or, more accurately, transposes the tracks routed to the Brain — transposing percussion tracks would be pretty silly, though it’s nice that it’s an option). Some more under-the-hood cleverness is also there to pick the best scale type for your transposition: e.g., if in C major, pressing a ‘D’ key will generally take things to D dorian. Naturally, all transposition work can be sequenced and arranged like usual, opening up some intriguing possibilities, and perhaps saving pattern space.

A single instrument track can also be linked to the Brain, with the latter passing through any note data. This lets you play (or sequence) more complex melodic riffs with the OP-XY doing its best to make your backing tracks in key with what you’re playing. Quite uniquely, there’s also support for polyphony, so you can punch in chord progressions and see your sequences respond, sometimes in rather subtle and clever ways — punch in a diminished 7th or sus4 chord and you’ll hear the changes even if the key stays the same. It’s a fun and simple way to get some melodic action in, and it’s especially great for live performance.

There are flaws with the system, though. For starters, teenage engineering’s made the decision to only use naturals and sharps in scale names, leading to some enharmonic wonkiness — who wants a nice dose of D sharp and A sharp major? More complex tracks with secondary dominants or modulations are also not handled too well, since the auto detection expects a single key per pattern. On top of that, the Brain locks the notes it outputs into a scale of its choice, meaning that it can’t be used as a simple transposition tool. If it wants to give you a result in F phrygian, that’s all you’re getting — it’s got a mind of its own! This means that you can’t quite force it to just take everything up or down a number of semitones, which would have been incredibly useful.

Punch-in FX are a beloved feature native to teenage engineering’s inexpensive Pocket Operator range. Both the OP-Z and OP-XY share an implementation quite similar to the original. With the sequencer running, shift-pressing any key on the keyboard while on an instrument track applies the chosen effect to either the current track or all tracks of the same type (that is, all melodic or all percussion tracks), with some effects only available in one case or the other. Punch-in FX aren’t just for live performance, and can be sequenced or recoded — though all punch-in FX data gets saved separately in a dedicated auxiliary track, unlike parameter locks.

There’s not a whole lot to say about the MIDI, CV and external audio tracks. These are as utilitarian as tracks get, and allow you to control outboard gear and route external audio in and out of your projects. There are a lot of utility tools packed in here. The MIDI track can also send MIDI CCs and has an LFO that can fiddle CC knobs for you. The CV track is simple and straightforward (and sadly, uses the same multi-out as MIDI, so you can’t have both at the same time — shucks). External audio options are extensive, with the first module dedicated to the external audio input, the second module dedicated to routing options for the auxiliary audio output accessible using the multi-out port, and third and fourth modules offering a filter and an LFO that can be applied to the incoming audio.

Finally, the tape track is a proper homage to the OP-1. By recording and continuously updating the last 16 steps’ worth of audio, tape keeps a continuous audio buffer — divided into 16 freely accessible segments that can be used to perform tape trick–style effects. Keys on the keyboard are used to access a segment, looping it for as long as the key is held. Speed and segment length is also tweakable, and the whole thing can be mixed with the main sequencer playback using the final parameter encoder. This is a feature we absolutely adore, even though it might not seem like much initially — and the track-based implementation of all the best bits of the OP-1’s tape goodness is nothing short of brilliant.

Some (early) firmware woes

The OP-XY hit the shelves in November 2024. Since then, there have been a number of updates, mostly aimed at squashing residual bugs and adding the occasional extra feature. Reading the changelog reveals just how much impressive work went on after the XY hit the shelves. It hasn’t always been smooth sailing — especially with some bugs in the early firmware causing crashes and even data loss — but currently, things are stable. It’s never a bad idea to have a backup or two on another device, but we haven’t had to recover from one yet. However, we have experienced slowdowns at times, UI weirdness that required us to reboot the unit, and a rather weird bug with playing fast, repeated chords that leads to some of them being dropped off or played late. Our guess is that the automatic voice assignment system gets confused at times.

There are also some UI bugs, notably with some of the auxiliary tracks’ modules (remember — the CV track’s LFO and a few other similar instances). Some step components have wrong descriptions in the UI, like the parameter, component and trig. While, e.g., the interface might say skip every -nth trig, what actually happens is that every -nth pass plays. This is expected behavior: it’s just the little pop-up text box that’s trying to confuse us all.

This is all to say that the OP-XY isn’t teenage engineering’s most stable device. But knowing the company’s track record with updates, we don’t really doubt that we’ll see everything ironed out in time (and that there are a whole lot of additional features on their way). Maybe the OP-XY could have spent a few more months under wraps, releasing with a more polished firmware version, but alas, things are improving fast — and most products have a rocky first few months.

Alternatives

It’s not an overstatement to say that there’s nothing quite like the OP-XY currently on the market. If you’re fully sold on the workflow, nothing else is going to scratch that itch. The closest you can get is the OP-Z, but — here’s the kicker — it’s been discontinued following the OP-XY’s release. A lot of resellers still stock it though, and second-hand units can be found in good condition for ~$400. We don’t need to mention much about the Z here as it’s been prominently featured during the entirety of this review (and if you still want more info, we’ve got a lovely write up dedicated to it). If you’re buying second-hand, watch out for some common defects, like double-triggering (caused by oxidative damage to the OP-Z’s little metal dome buttons), pitch-bend pad flakiness (the piezo circuitry in the Z sometimes degrades with time) and chassis warping.

If you’ve been following along so far, you should be aware of the differences between the OP-XY and the OP-1 field, so you should know if one interests you more than the other. Again, if you need some more reading fodder (ooh, another shameless self-plug), we’ve got an article on the OP-1 that should contain some interesting info. In a nutshell, picking between the two is all about choosing either the XY’s precision-oriented workflow or the OP-1’s wackier, more immediate and undoubtedly more iconic one.

But what about third-party options? The deep sequencing capabilities immediately bring Elektron boxes to mind. Depending on your preferred flavor, these go for ~$1000 a pop. They’re nowhere near as portable as teenage engineering’s offerings and aren’t battery powered, so they’re suited for more permanent setups. And do keep in mind that no singular Elektron box covers all of the OP-XY’s features as they tend to focus on either sampling or synthesis (though picking up more than one, e.g., a Digitakt II paired with a Digitone II could match, and at times, even surpass the functionality).

On the other hand, they’ve got their own fun quirks and an array of extremely powerful and deep features — most Elektron models offer unmatched depth in their field of choice and come with a workflow that many swear by.

DAWs are generally capable of what hardware can do and then some, and for the OP-XY’s asking price, you can land yourself an M4 Max Mac Studio or an M4 Pro Macbook Pro and still have some cash left over for a copy of your favorite DAW or a MIDI controller. Or if you go the iPad route…

…we’ve already said this about the OP-1 field, and we’ll say it again. Sure, the above option would be a lot more capable (and dare we say, practical) — there are composers and producers who make a living with in-the-box setups, but it’s just not the same experience that a physical groovebox (or any other bit of gear) gets you. Some people go DAW-less for a reason. If the OP-XY meshes perfectly with your creative sensibilities, it’s a worthwhile investment. If you want the portability, if you want to embrace the unique limitations and features, and if hardware inspires you, well, there’s your answer.

There are many other small music-making options on the market too, each with a distinct feature set and flavor. Offerings from Polyend, like the excellent Tracker; the Synthstrom Deluge; the Dirtywave M8 — all of these have their own pros and cons. In our opinion, the OP-XY is the most complete and versatile tool of the lot, but that’s not to say that there aren’t certain things that the competition doesn’t, at times, do better.

Verdict: who’s the OP-XY for?

The OP-XY isn’t cheap. Not one bit. At $2299, it’s a sizable investment. And that makes it really difficult to come to any definite conclusions because, for some people, it’s just the thing they’ve been waiting for, while for others, getting one will just seem frivolous. It’s a wonderful on-the-go music-making tool, with enough connectivity to be your studio’s jamming centerpiece packed with all the features that make it an excellent live performance instrument. There’s a lot to love here, though it’s definitely not a good candidate for a beginner’s-first-instrument. There is more essential gear to be had early on in your music-making journey that’ll set you back a lot less than the OP-XY.

Over the course of this review, we’ve explored and documented just about everything that the OP-XY can do and there’s likely more that even we don’t know about. It’s powerful. And it’s just about the best portable sampling and sequencing setup you could wish for. And it’s so fun to use! Like all teenage engineering gear, it’s a tool with an associated concept — and your relationship with that concept determines how much use and enjoyment you’ll get out of it. So, research as much as you can. Get hands-on with one if you get the chance. See if it’s right for you and whether it speaks to you. This little device can facilitate thousands of hours of creative exploration for many, many years to come.