Mixtile Blade 3

The Mixtile Blade 3 is far from being a mature system, but multiple great ideas alongside powerful hardware make it one of the more promising SBCs we've taken a look at lately. While expensive for its current set of capabilities, that of a regular SBC, we're optimistic that the Mixtile Blade 3 will soon become much more powerful as software support becomes more and more mature and as features slowly get released.

Pros

- Great performance thanks to the RK3588

- Lots of RAM and eMMC on-board

- (Potential) future native cluster support

Cons

- Much more expensive than comparable boards

- Software support is still early and sparse

- No wireless networking on-board

- Annoying official case

The Mixtile Blade 3 began its journey as a crowdfunded project, presenting to the world in its May 2022 Crowd Supply campaign. Showcasing this new board as a stackable, high-performance Pico-ITX SBC based around Rockchip’s RK3588, early marketing placed a lot of focus on the cluster features utilizing the U.2 edge connector, enabling the scalable ARM-based servers.

Pico-ITX, the standardized 10 x 7.2 cm motherboard format was announced by VIA Technologies in January 2007 and presented at CeBIT the same year. As one of the smallest motherboard form factors available at the time, Pico-ITX was quickly accepted by automotive computer manufacturers. Around this time, it also found numerous uses in miniature media centers and small home servers. Becoming standard in industrial IoT applications where space is limited, there’s a wide range of mounting options and accessories for boards of this size.

Mixtile Blade 3 hardware overview

Our Mixtile Blade 3 review unit, kindly provided to us by the company, arrived in its optional $35 custom aluminum black case and had Debian 11 preinstalled. Before any testing, we decided to crack open the case to get a decent look at the board itself. Undoing the four screws holding the case’s backplate is a simple enough task, but their position under four rubber feet is less than ideal. In order to open the case, which won’t be a rare occurrence at all – we’ll explain this later – you’ll have to remove the rubber feet and stick them on again. Needless to say, this isn’t the best for the adhesive holding them in place, especially when there aren’t any spares included.

The package also includes a small suction cup which serves double-duty as both a handle for lifting out the Mixtile Blade 3 out of its shipping box, and (presumably) as a tool for aiding in backplate removal. Sadly, this little suction cup just could not manage to get a solid enough grip on the textured metal, forcing us to resort to prying the backplate off. This also wasn’t as easy as it seemed, as precision machining meant there was no space for us to lodge a spudger into, so we had to resort to MacGyvering our way inside, using one of the screw holes for leverage. This was pretty difficult to do without marring the surface finish. After finally cracking the case open, we saw what was holding us back: a tacky silicone thermal pad facilitating heat transfer between the main SoC and this plate itself.

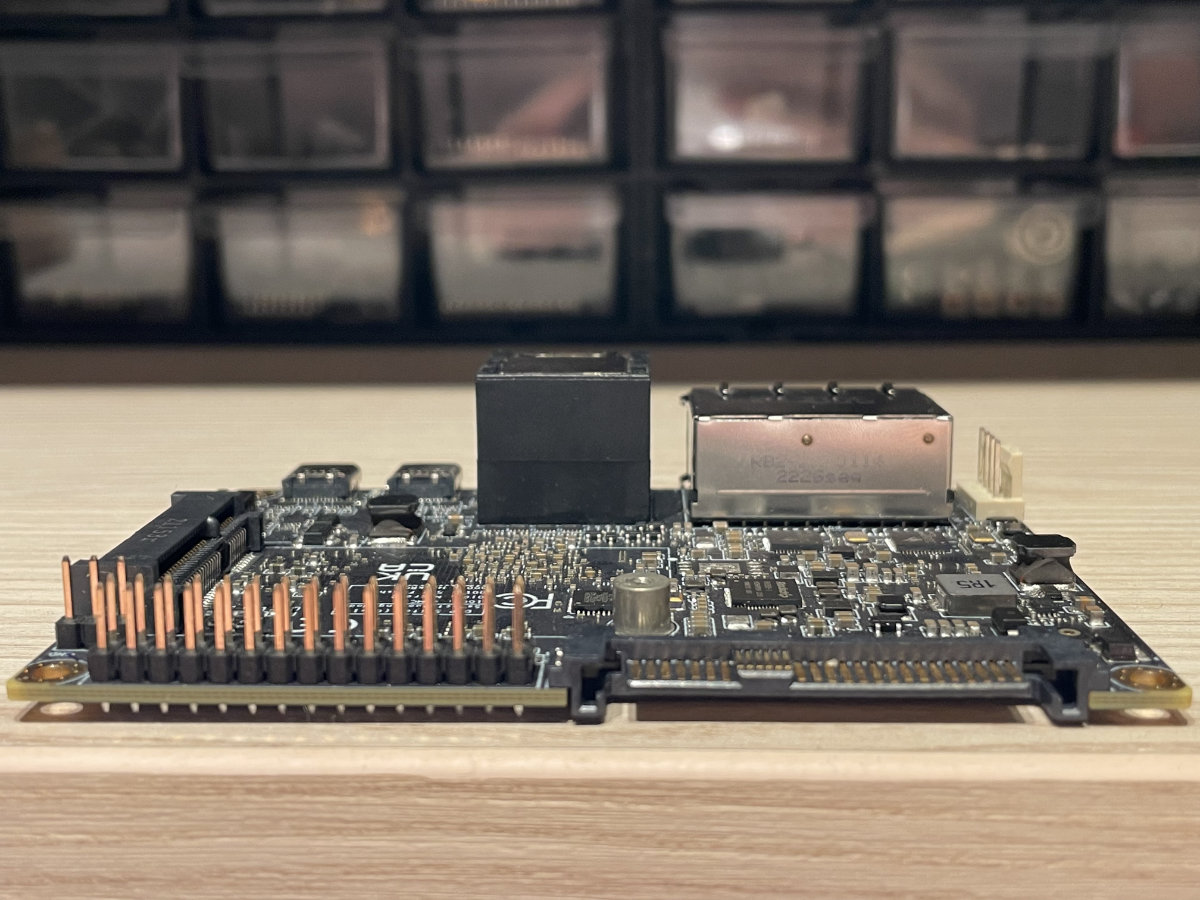

The elegant gold-black PCB color scheme immediately caught our attention, as did the high-quality white silkscreen print. Interestingly, the relatively large RK3588 SoC is mounted on the bottom side of the board – that is, the one facing us now. This is a powerful octa-core ARM chip, with four Cortex-A76 and four Cortex-A55 cores, along with a Mali G610 MP4 GPU and a custom tri-core NPU, delivering up to 6 TOPS of compute.

While the chip itself is officially rated at 2.4 GHz for the A76 cores and 1.8 GHz for the A55 cores, we’re starting to notice some variation between different units, something which has been reported back in 2022 on the Radxa forum, and has been traced to Rockchip’s proprietary frequency control systems, ultimately a form of silicon binning. While we’ve seen a “perfect” RK3588 with its big cores clocked at 2400 MHz (well, a RK3588S to be precise) in the Orange Pi 5, our Mixtile’s RK3588 seems to only reach 2304 MHz. We’ll explore whether this has any effects on performance shortly.

Right next to the SoC are two 2133 MHz LPDDR4 RAM chips made by Micron and a 128 GB SanDisk eMMC 5.1 flash chip. This makes our test unit the highest-end one currently available, retailing for $369. The bottom side of the board also hosts a MIPI-CSI camera connector. Sadly, there’s no cutout in the official Mixtile to pass this cable through, which is a bit of an omission.

Another set of screws is preventing us from reaching the top side of the Mixtile Blade 3 board. Undoing these lets us also see deeper into the case, revealing a small fan directing the airflow through a set of radiator fins on the inside. We found this fan somewhat loud, but decently efficient. The more observant among our readers will have noticed the fact that the processor and the fan are on the opposite sides of the board, meaning that there’s no direct airflow over this heat-producing chip. The idea here is – apparently – to have the RK3588 sink as much heat as possible into the backplate, have that heat carry over through the case to the top case piece, and then dissipate as much heat as possible with the help of a fan.

This does make the whole case get really toasty (painfully toasty, at around 60 °C!) during use (as most of the metal has to warm up quite a bit to effectively dissipate the heat), but by some miracle, there’s no thermal throttling at all, even after more than an hour under full load. After around 120 minutes, the temperatures settled at 82.2 °C as measured for the big cores and 80.4 °C for the small ones and never increased further. During this test, our ambient temperature was around 29 °C, which was definitely a bit warmer than usual.

Finally taking the Mixtile Blade 3 out of its case, we’re noticing that the U.2 connector has a daughterboard attached to it, used for attaching an M.2 NVMe SSD. In our tests, we managed to hit up to 2285.95 MB/s read speeds on our 256 GB Kingston NV2 SSD (rated at 3000 MB/s itself). Proper PCIe support allows this RK3588-based board to achieve almost 15 times the built-in eMMC performance when using NVMe storage. Logically, an SSD seems like a worthy investment, but the case implementation leaves a bit to be desired again. By mounting the SSD vertically, it effectively “sandwiches” it between the daughterboard and the aluminum side plates, cutting off air circulation and allowing it to heat up to somewhat unhealthy operating temperatures.

The U.2 connector itself is an interesting and very well thought-out-choice. On one hand, it’s easy to attach M.2 devices with a simple adapter, as both connector formats offer four PCIe lanes, as well as separate SATA lanes. While identical in data transfer performance, U.2 was originally designed for industrial applications and servers, where native support for larger 2.5” and 3.5” formats was required, as well support for hot-swapping, which is essential for large rack-mount server equipment. Finally, U.2 ports can provide 12 V power in addition to 3.3 V which M.2 ports utilize.

Next to this interesting port is a 30-pin GPIO header. While 10 pins short of the now-standard “Raspberry Pi” 40-pin header, it still tries to maintain partial compatibility by arranging the present pins in a rather similar manner.

Nearby, there’s a mini PCIe 2.1 slot meant for a networking card, since the Mixtile Blade 3 offers no wireless connectivity to boot. Do keep in mind that the official case has no antenna mounting points, however.

Right below is an SD card slot. It’s a standard friction-fit slot, but it’s bafflingly oriented towards the inside of the board. This means that it’s impossible to access this slot from the side, even if the case featured a cutout – which it doesn’t. Given that SD cards are the traditional way of installing operating systems on SBCs, this design choice leads to even more superfluous amount of case dismantling.

The board also features an UART debug header.

We’ve left the most interesting side for the end. The back of the board features two Ethernet ports. We commend the fact that both of these are of the 2.5 Gbps variety – no compromises were made here. There are two USB 3.2 Gen 1 USB-C ports, one of which is mostly dedicated to powering the board, and the other of which supports the DisplayPort over USB protocol. These are the only two USB ports onboard, one of which is realistically available, which definitely necessitates the use of hubs for desktop use (taking a page out of Apple’s book, perhaps)?

The Mixtile Blade 3 is a demanding SBC to power, requiring a high-quality 5V/4A power brick. RK3588-powered SBCs are oftentimes hard to power, but most of them manage to run just fine off of quality 3A supplies.

Between the Ethernet and USB ports are a pair of HDMI ports. One of these is an HDMI 2.0 RX input port, and one’s an HDMI 2.1 TX port. Even though the RK3588 has capabilities for two HDMI outputs, we still consider Mixtile’s set of media ports adequate, given the USB video out capabilities. The HDMI output port here can handle 8K60 video, while the input can encode 4K60 streams.

With our little hardware safari out of the way, we could finally pack the board back into its case. A cute blue status LED greeted us and the system very quickly booted up. A power button is also provided, which sounds like a given but is often an overlooked detail in SBC case designs, perhaps taking inspiration for the Raspberry Pi’s noted distaste for power buttons.

Software support

Our Blade 3 came with Debian 11 preinstalled on its eMMC. This OS is the only official one, and as of the time of writing, the latest release was published on the 5th of May. Officially, Android is also planned, but isn’t available yet. Updating Debian is also simple through Rockchip’s development utility (RKDevTool) and is a matter of simply connecting the SBC with a USB cable to a host computer. Updating the OS using an SD card is also possible, however, we’d avoid it as it requires opening the case up (not again…) – putting even more wear on the tiny rubber feet.

Debian 11 is fully functional and comes with a lot of installed software. CPU performance is top-notch, as we’ll see further below, but there seem to be some issues with the GPU driver, as we kept getting subpar graphics benchmark results. This is why we’ve opted to re-benchmark the unit using “unofficial” OS images. These are all offered on Mixtile’s website, but are created by third-party teams helping out with the project. Currently, there’s two systems available, Armbian and Ubuntu. Both of these use Linux Kernel 5.10 with Wayland and GNOME. Both of these also have functioning Panfrost drivers which manage to get around 15% better results compared to the Debian drivers.

The issue here is the initial installation method for these systems. Every time you want to change the OS, you’ll have to rely on Rockchip’s MASKROM mode. In order to get access it, it’s necessary to open the case up and extract the board in order to access its topside (that’s eight screws), and flip one of the physical DIP switches over. With the board out of the case, it’s time to use RKDevTool again in order to flash the new OS, and then return the DIP switch back to its original position before packing everything up again. Every. Single. Time.

Still, this is again more of a complaint about the board case than the Mixtile Blade 3 itself, or even these OS images, as utilizing the MASKROM mode is a standard procedure for Rockchip processors.

Performance and benchmarks

After glancing at all the hardware, let’s take a look at how it actually performs. With our Mixtile’s SoC A76 cores clocked at 2.3 GHz, as mentioned before, it’ll be interesting to see if there are any performance drawbacks compared to other RK3588-based systems.

Starting with Geekbench 5.4.4 results, we get strong performance, as expected. With 650 points in the single-core test and 2620 in the multi-core one, it’s a strong contender, not lagging behind any other of our boards.

Sysbench’s CPU test also returned great results. Given that this test relies on simple operations and is quite dependent on processor speed, we were pleasantly surprised to see the results in check with all of our other boards.

ARM’s cryptography accelerator is notoriously similar in most of its modern cores. Sharing the clock with the rest of the CPU, this crypto accelerator is so consistent in its performance per MHz metric that it’s somewhat amusing. The Mixtile Blade 3 delivers strong performance, but is a few percent behind other RK3588-based boards with chips running at 2.4 GHz. It’s worth noting again that the A55 cluster remains unchanged at 1.8 GHz, making the actual performance drop even smaller than the ~4% drop suggested by the big cores’ clock.

The LPDDR4 RAM clocked at 2133 MHz is plenty fast. Both Sysbench RAM and tinymembench give us pretty good results, miles ahead of slower RAM found in many older boards.

In fact, tinymembench results were so similar to some other boards we had on hand that we had to check the exact part numbers of the chips. Wouldn’t you know it: the Orange Pi 5 both uses Micron’s D9ZCL chips (whose part name is MT53E2G32D4NQ-046) while the Mixtile Blade 3 uses Micron’s D9ZRD chips (MT53E2G32D4DE-046). These are nearly identical in specs, which explains our benchmarking results, too.

Unixbench results are expectedly great. Thanks to the case (we know, after all our whining, but the case does in fact keep the board’s temps under some sort of control) we’re seeing the full extent of the RK3588’s performance. Both single- and multi-core scores are better than in systems with no built-in cooling. We’re getting comparable results to the Orange Pi 5 with the ICE Tower cooler block. Again, the 4% drop in clock speeds here does not translate to a visible performance loss. Benchmarks in general are not precise enough to detect such small differences, and clock speed isn’t the only part of benchmark result variation (as an extension, clock speed also isn’t the only part of silicon lottery, either, as various parts in a chip can turn out slightly better or worse).

Finally, Octane 2.0, a test which we use only as a rough indicator of performance, and still keep around for legacy comparisons. As inaccurate and software-dependant as Octane is, it does tend to accurately depict the desktop user experience in light day-to-day tasks. Higher scores on this test generally mean a more fluent OS. For the Mixtile Blade 3, the best Octane score was measured with Ubuntu 22.04, mostly due to better driver optimisation.

Conclusion

The Mixtile Blade 3 is a well-made computer, primarily designed for clustering. This is the main idea behind the inclusion of the U.2 connector, along with another daughterboard meant for interconnecting several Blade 3 units using custom-made PCIe cables utilizing SFF-8643 connectors (offering much better cluster performance than traditional Ethernet-based clusters), as well as providing a SATA 3 connection and a 12V 6-pin power connector.

Currently, however, the Mixtile Blade 3 is only useable as “just” an SBC computer, which is why we didn’t mention much about its planned cluster functionality earlier during the main review sections. 16 GB of RAM and 128 GB of eMMC, as well as great external storage connectivity are all major elements adding up to quite an appealing package, viable as a tiny ARM-based server, media center, or even a desktop replacement.

The official case gets a bit in the way with some annoying quirks and sub-par thermal performance, but is visually appealing and handy for some applications. Ultimately, our quips with it aren’t directly aimed at the Blade 3 board itself, the real focus of the review, so we can’t nitpick too much.

However, the RK3588-based SBC market is saturated, and the Mixtile Blade 3 is one of the more expensive options available (quite a bit more expensive than most, in fact). We are eagerly awaiting the release of the cluster software (and additional hardware, if necessary), as this feature would single-handedly set the Blade 3 apart from basically every other SBC available, more than justifying the premium.

It’s still very early days for the product, however, and the whole offering is just a bit rough around the edges. There’s still a long way to go for the team to fulfill all of the initial promises, but what we’re seeing so far is exciting.

More information: Mixtile Blade 3 site